News & Events

Memorizing Shakespeare to master the bard’s major works

Associate Professor Ann Christensen of the Department of English writes about why performing Shakespeare helps her students better understand his poetry and prose.

A student's catalog of familiar phrases originated

by Shakespeare

“Quite apart from the video technology now at our disposal . . . we have a simple but effective instrument for teaching and enjoying Shakespeare: the human voice.”

~ Coppelia Kahn, “Letter from the President,” Shakespeare Association of America Bulletin 2009.

As an instructor, I have found the three-hour final exam slot of limited pedagogical value, a realization that evolved over twenty years in the classroom. I decided to rethink what to do with the dedicated exam slot after watching some of our best-prepared students literally tearing their hair out as they scribbled in a blue book, stressed and anxious about ‘performing’ within the time limit. Some students tell me of feeling faint or even having to leave to the room in order to vomit during a high-pressure exam! This kind of strain, for me anyway, was not a good way to end a semester otherwise devoted to genuine intellectual exchange. So, I seized on the term “perform” and I now use my final-exam time for students to perform some Shakespeare-related piece. We gather, have cookies or coffee, and hold an informal, often hilarious, sometimes poignant session using our voices, bodies, books, and other props to culminate our semester’s study of “Shakespeare’s Major Works” in English 3306.

As for the cumulative work that an exam does, I assign a reflective portfolio, in which students reflect on their development as writers, readers, and critics of Shakespeare and present a sample of their best writing. This assignment, more common in Composition and Creative Writing classes than in Literature, requires the same level of preparation as an exam: reviewing the semester’s material and making connections; but it also demands that students reread their own work along with my comments, and genuinely reflect on their scholarship. So the in-class activity complements the individual work of review and self-evaluation. This combination works well and I get original and insightful papers and performances – and no vomiting or hair pulling.

Educators and orators have long held the virtue of memorization as an aid to learning and “owning” the material. For example, my late mother who studied Shakespeare only in high school in the late 1940s, could still recite Portia’s “quality of mercy” speech as recently as five years ago! Since Shakespeare wrote plays that actors have memorized and spoken for centuries, it seems hardly a stretch to use these techniques in class. Yet, when faced with his output of thirty-six plays, 154 sonnets, and a few narrative poems, coverage is crucial. How much can we cover in a sixteen-week semester? According to Kahn, former President of the SAA and Professor of English at Brown University, reciting the lines helps students “understand and appreciate what the words mean through hearing how they sound.” Armed with this justification, I ask students to commit to memory one fourteen-line sonnet.

But I do provide guidance, and I also permit other creative responses to the task. My colleague and friend, Kate Pogue is an actor, director, and long-time HCC and UHD instructor of drama, as well as the author of three books on Shakespeare’s life and work. She helped me design a tip sheet for memorizing verse. For example, iPhones and other technology permit students to record their own voice (and also listen to professional recordings) of their chosen material. Some tried-and-true advice for memorizing and rehearsing that Ms. Pogue and I have developed:

- Write down the sonnet over and over; this ties into kinesthetic learning. (My students had the option to write out their poem in class rather than performing it—proof of their memorization but no pressure to perform. Very few take this option.)

- Speak it out loud again and again in many different ways-- fast, slow, emphasizing the caesura or pause in a line, emphasizing the last and first words of each line, shouting the whole sonnet, whispering the whole sonnet, alternating whispering and shouting each line, “chewing” or exaggerating the consonants and extending the vowels, emphasizing assonance and alliteration. (This helps students to hone in on the sonnet’s structure.)

- Once you know what it means, recite it into your phone or other device so you can listen to it and recite along with it over and over again.

- Make up a situation for the speaker and his/her relationship to the recipient. Shakespeare’s lines and students’ imagination makes critical reading come to life. John Barton, long-time director for the Royal Shakespeare Company, calls the sonnets “mini-dramas,” each telling a story in miniature.

With this pedagogical foundation established and the resources in hand, our final exam slot relieved rather than caused stress.

Students invented and explored countless “mini-dramas.” Over the past semesters I have seen Shakespearean sonnets appear though tearful break-ups, name-calling tirades, half-hearted apologies, a Hollywood agent losing her “talent” (“Farewell, thou art too dear for my possessing”), a hand-wringer spoken by an anxiety-ridden mother, a sloppy phone message left by drunken ex-boyfriend, a troubled politician unable to sleep. Each scenario demonstrated its own power and possibility and stayed “true” to Shakespeare.

Among the imagined scenarios enacted by this fall’s class was a parent urging her son to go out and produce some grandchildren already (“From fairest creatures we desire increase”), Anne Hathaway writing to her husband away in London, a grieving relative, a tortured clergyman, a cat addressing her long-time enemy, a stuffed dog. And even a Bob Dylan homage: Hadley Hollingsworth parodied the classic Dylan video of “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” Just as the singer tosses his witty lyric-posters aside during the song, she’d done some original line drawings and let them fall as she hip-hopped her way through a sonnet. But props and costumes were icing on the cake because the real show came from their insights into Shakespeare’s work and the relevancy they see in contemporary culture.

Giselle Andujar provided a fitting conclusion in a rap romp charting our progress from our first poem, “The Rape of Lucrece,” through tragedies, comedies, and histories to The Tempest: “The sonnets gave way to the turn around the bend / And now our Shakespeare class has come to its end.”

- Ann Christensen

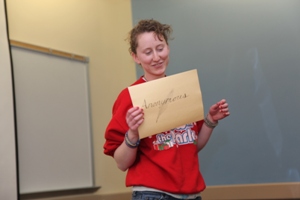

Scenes from the final-exam performances in English 3306: Shakespeare’s Major Works, taught by Ann Christensen, associate professor of English:

Jonathan Sanford in a friar's habit |

Hadley Hollingsworth parodied the classic Bob Dylan video of "Subterranean Homesick Blues." Just as the singer tosses his witty lyric-posters aside during the song, she'd done some original line drawings and let them fall as she hip-hopped her way through a sonnet. |

Jennifer Fox appeared in Renaissance regalia |

|

Students in the Fall 2011 course English 3306, Shakeskeare's Major Works, taught by Ann Christensen, professor of English |

Associate Professor Ann Christensen and Shakespeare-inspired photo montage. |