Data from Cassini Mission Enabled New Findings

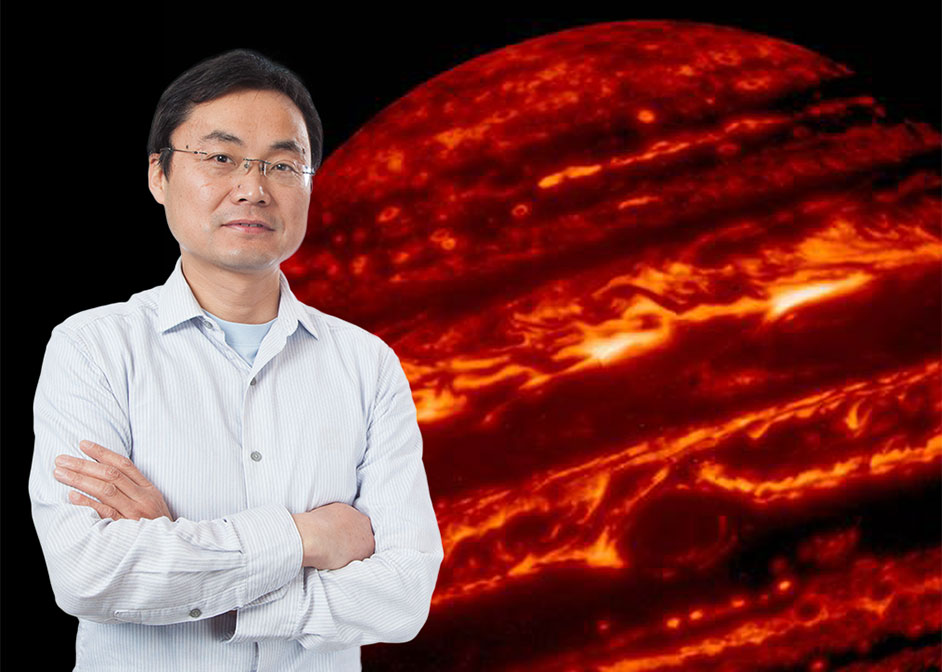

In a recent paper published in the journal Nature Communications, University of Houston associate professor of physics Liming Li and associate professor of atmospheric science Xun Jiang, along with collaborators, report that the amount of energy reflected from Jupiter, along with its internal energy, is higher than previous estimates.

Photo credit (Jupiter): Gemini Observatory/AURA/NSF/UC Berkeley.

Photo credit (Li): Chris Watts

“This will help us better understand how Jupiter was formed,” said Li, who is a faculty member in the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics.

Reflected Solar Energy Higher Than Previous Estimates

Every day, a certain amount of solar radiation hits Jupiter. Some of this light is absorbed, some is reflected. The amount of light that is reflected versus absorbed determines a planet’s temperature. This ratio of absorbed versus reflected light also help us estimate the internal heat, which plays a critical role in shaping Jupiter’s formation.

Previous estimates calculated Jupiter’s amount of reflected light to be roughly 30 percent. These analyses were performed using data from the Pioneer and Voyager missions, which launched in 1973 and 1977.

New estimates, performed by Li, Jiang, and collaborators, estimate the amount of reflected light to be around 50 percent. These estimates were based on data collected during the Cassini mission, which was launched in 1997, with a final destination of Saturn. From 2000 to 2001, as the Cassini spacecraft flew by Jupiter, it collected measurements about the amount of reflected light, as well as its wavelengths.

This data, which was in greater detail than previous missions, allowed for a more complete analysis of the overall radiant energy budget for Jupiter.

Internal Energy Production Higher, Affects Planetary Conditions

Li, Jiang, and collaborators also calculated the amount of internal energy generated

by Jupiter.

Internal heat is energy that is generated from within a planet, and has the potential

to contribute to a planet’s overall temperature. On Earth, internal heat is negligible,

contributing only a small amount to overall global temperatures.

“During the formation and evolution of Jupiter, you had heavier elements that sank down, releasing potential energy during the process,” Li said. “This internal heat, which mainly comes from the released potential energy, can help us better understand how the giant planets were formed.”

Their finding was that Jupiter produces more internal energy than what was previously thought.

“The story for Jupiter has changed,” Li said. “This study also forces us to re-examine the radiant energy budgets and internal heat of other giant planets in our solar system.”

- Rachel Fairbank, College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics