Research Focused on Understanding Role of Autophagy in Late-Stage Prostate Cancer

According to the American Cancer Society, an estimated 1 in 7 men will develop prostate cancer during their lifetime, with prostate cancer being the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States. In 2016 alone, there will be an estimated 180,890 new diagnoses of prostate cancer.

Autophagy’s Role in Cell Maintenance

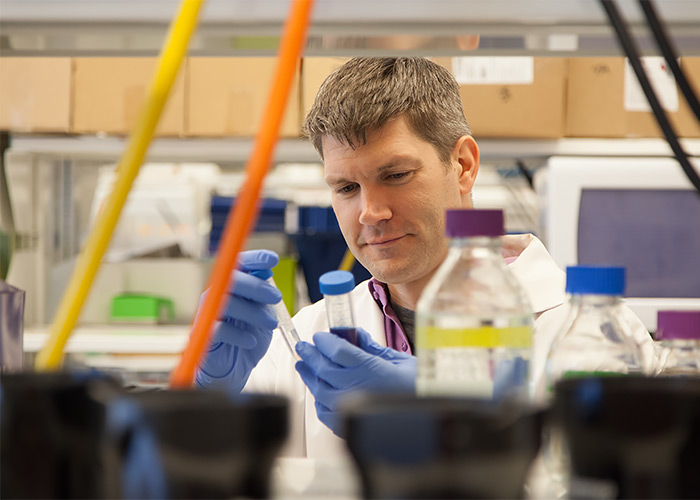

Daniel Frigo, assistant professor of biology and biochemistry, was awarded a $792,000

grant from the American Cancer Society.Daniel Frigo, assistant professor of biology and biochemistry at the University of

Houston, was awarded a four-year, $792,000 grant from the American Cancer Society.

This grant will support his efforts to define the role that autophagy, a cellular

process described as “self-eating,” plays in the initiation and progression of prostate

cancer. Answering this question will help determine whether autophagy is a viable

target for potential cancer therapies.

Autophagy is a process in which cells break down and “eat” parts of their own cellular machinery. This process serves several important functions. The first is the breakdown and recycling of worn-out organelles or unused macromolecules (e.g. proteins, fats, etc.). A second role is keeping cells alive during times of famine. When nutrients are scarce, autophagy can break down parts of the cell to use as much-needed fuel or building blocks.

Autophagy a Potential Target for Cancer Therapies

“In cancer, autophagy may function as a double-edged sword,” said Frigo, who is part of the Center for Nuclear Receptors and Cell Signaling in UH’s College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. “In the early stages of cancer, autophagy is thought to act as a tumor suppressor, as it can slow down or stop the cell cycle during times of stress. However, if you look at the late stages of cancer, autophagy appears to have the opposite effect, by promoting the progression of cancer.”

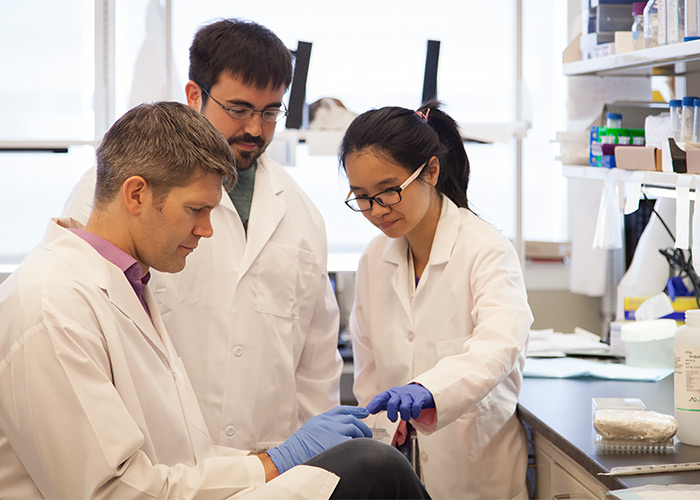

Frigo, shown with lab members Thomas Pulliam and Chenchu Lin, studies the role of

autophagy in prostate cancer.Blocking autophagy offers a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of late-stage

cancers. In the past decade, numerous clinical trials have tested existing drugs that

block aspects of autophagy as potential cancer therapies. However, to date, these

clinical trials have to date yielded inconclusive results.

This is likely due to the fact that the drugs tested inhibit a step in autophagy that is also involved in other cell processes. In other words, these drugs are similar to using a ten-pound cannonball to hit a tiny bulls-eye. The drugs would hit the intended target – autophagy in prostate cancer – but only by causing damage to related processes.

Looking For What Activates Autophagy in Prostate Cancer

“If we can find out what is activating autophagy in prostate cancer, then this might give us a more selective target,” Frigo said.

Finding a more selective target could allow for the development of drugs that attack prostate cancer without causing severe side effects. For this to be achievable, more information is needed.

“We still don’t fully understand the role autophagy plays during the different stages of prostate cancer,” Frigo said. “We want to take a systematic approach, using both genetic and molecular techniques, to answer this question.”

Frigo and his research team will be examining autophagy in mouse models of both early and late-stage prostate cancer. Suppressing autophagy at these different stages – and examining the effect this suppression has on cancer progression – will offer insight into its role.

In addition to these experiments, Frigo will also be conducting preclinical trials to test the efficacy of a next-generation inhibitor of autophagy.

The preliminary research for this grant was made possible by funding from a UH program, Grants to Enhance and Advance Research, as well as grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Golfers Against Cancer.

- Rachel Fairbank, College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics