UH Associate Professor’s Book Amplifies Voices of Incarcerated Individuals

Posted Sept. 8, 2022 — Why do you look so surprised? You thought prison would define me?

The opening lines of a poem by James Adrian, who wrote the verse while in prison, prove the power of literature to defy circumstances.

You thought my potential would get lost in this crime spree, or the magic in my pen would mysteriously run out of ink, & I would never find a way to articulate what I think?

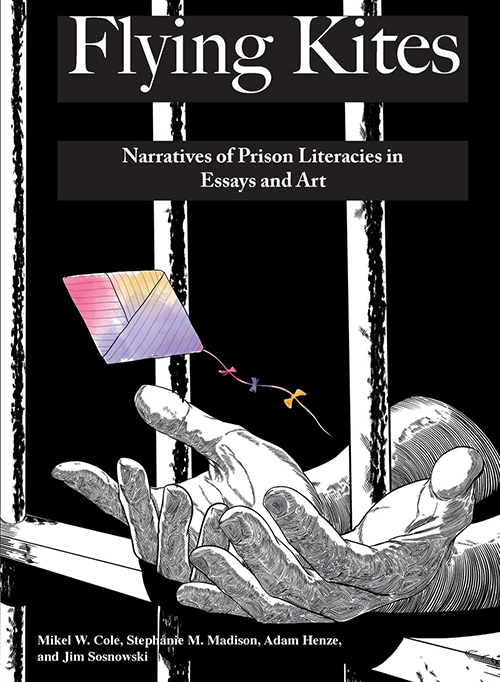

Adrian had the opportunity to tell his story as part of the book “Flying Kites: Narratives of Prison Literacies in Essays and Art,” co-edited by Mikel Cole, an associate professor at the University of Houston College of Education. The book sheds light on the realities of mass incarceration in the United States and how literacy and literary expression can change that. Most chapters were written by people currently or formerly incarcerated or in immigrant detention facilities, while scholars working with the marginalized population also contributed.

Cole and his co-editors — Stephanie Madison, Adam Henze and Jim Sosnowski — all do work related to literacy among imprisoned populations, including through poetry workshops and English as a second language programming. But “Flying Kites” isn’t about their own work.

“We decided early on we were not interested in the spotlight for ourselves so much as we were interested in using our platform to pass the mic to amplify the voices of folks who are incarcerated,” said Cole, whose research focuses on multilingual learners.

The editors are donating their royalties to El Refugio, a nonprofit that facilitates visits to immigrants and asylum seekers detained at Stewart Detention Center in Georgia. A GoFundMe webpage was also set up to raise money to send the book to incarcerated people.

Learn more about Cole and “Flying Kites” in this Q&A, which has been edited for clarity.

What are the visits to the detention centers like?

Every time we ask (immigrants in detention) what they need, a couple things come up. One would be books. You can’t bring a book to them. It has to be shipped from a publisher so you’re not passing files, razor blades or other contraband through the books.

The other thing they consistently ask for are ESL classes because, for many, English is not their first language. Guards are speaking in English, and if they don’t comply quickly enough, they get punished. They use solitary confinement like tired parents use timeouts. All the legal proceedings are happening in English. The judge speaks in English. They would ask for ESL classes, and ESL/bilingual education is my background, so that’s my connection to this work.

What is the inspiration for the book’s title and cover?

A kite is a message prisoners pass to each other, and they will often fold it into small pieces and pass it to other people using rubber bands or by hand. So, to fly a kite means to pass a secret note to another prisoner in prison. But the idea is passing the note not to each other but to folks outside prison to let people know what life is like for them. The hands and kite on the cover convey the heart of this book: to feel heard in a space that intentionally tries to silence them.

What should people know about immigration detention facilities?

I think most folks do not understand what immigration policy and immigration enforcement really look like. You hear, “Why don’t you get in line and do it the right way?” There isn’t a single pathway through immigration. Some come through a lottery system. Others may come in if they are sponsored by an employer or if they come in with enough money to invest in a business. It’s really hard to do immigration legally. Even if folks do that, it could be a multiple-decade-long process.

Since 9/11, criminalization for the immigration process has skyrocketed. Immigration detention centers just exploded following 9/11, and in conjunction with the growth of private prisons and detention centers, there is now a business incentive. High security prisons have contracts with ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement), and they have to keep beds full to fulfill contracts. Maybe previously, these immigrants might have been arrested and released pending their court date, but they’re now instead arrested and detained.

How did COVID-19 complicate the book’s progress?

Getting the call for submissions to incarcerated authors right as COVID appeared was really difficult. Suddenly, no visitors were getting in or out (of the prisons and detention centers), which really slowed the book’s progress. The ability to use phones was restricted. Three years later, we’re still not back doing poetry workshops in Stewart because the facility is still closed (to visitors).

We did more editing of the pieces than we would have liked because we could not get them back and forth to the authors frequently enough to let authors drive the editing process.

COVID has impacted every facet of the book and even the ability to promote it. It is as if the universe wanted it to exist despite all these hurdles.

What makes this book important?

A lot of the work done by scholars is written in academic language and with academic theoretical frameworks, data and analysis. It is written for other scholars. There’s a whole other genre by incarcerated folks that speak firsthand about their experiences. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” is an example of that. This book lives between those genres. What really marks this book as unique is the first-person experience of having been detained. That is the heart of this book.

Was there a part of the book that really spoke to you?

Kodi Faircloth (“Snapshots”) is blind, so in addition to all the normal access issues that come for her, the process of her writing her piece meant having this friend transcribe what she was saying orally. The dedication, the persistence, the tenacity it takes for her to write something anyway, coupled with the commitment of that friend, that relationship is just really powerful.

What motivated you to complete this book?

It’s impossible for any one person to be involved in everything that needs our attention. We’ve got climate issues, mass incarceration issues; we continue to have gender issues, racial issues. It can be overwhelming. It can be like, “Oh my god, where do I start? Anything I could do feels so small in the face of the enormity of it all.” But I would hope that people reading this find their thing, whatever that is. Because it is absolutely true. The enormity of the work that needs to be done is too much for one person. It really takes all of us doing small things.

— By Lillian Hoang