International Team Deploys Unmanned Submersible to Map Underside of Glacier

An international research team deployed the unmanned submersible, ‘Ran,’ underneath 350-meter-thick ice. They got back the very first detailed maps of the underside of a glacier, revealing clues to future sea level rise.

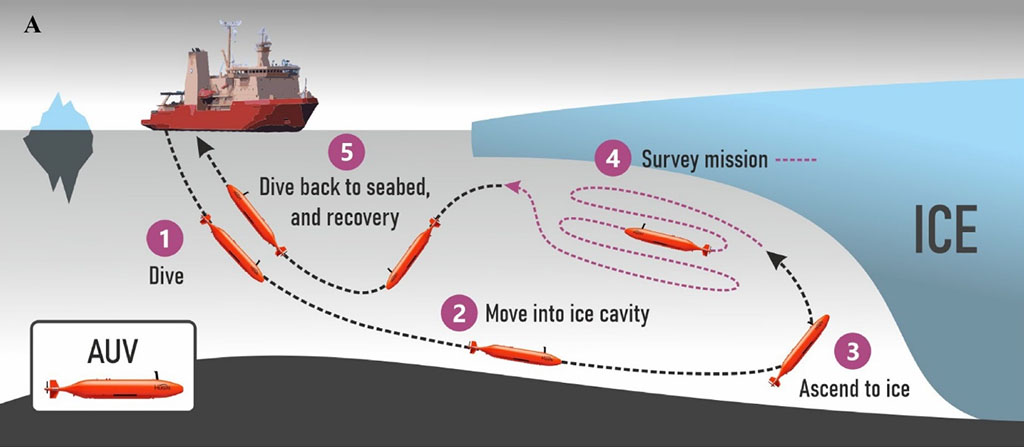

Ran, an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), was programmed to dive into the cavity of Dotson Ice Shelf, West Antarctica, and scan the ice above it with an advanced sonar. An ice shelf is a mass of glacial ice, fed from land by tributary glaciers, that floats in the sea above an ice shelf cavity. For 27 days, the submarine travelled a total of over 1,000 kilometers back and forth under the glacier, reaching 17 kilometers into the cavity.

“Like Seeing the Dark Side of the Moon”

“We have previously used satellite data and ice cores to observe how ice shelves change over time. By navigating the submersible into the cavity, we were able to get high resolution maps of the ice underside. It's a bit like seeing the back of the moon for the first time,” says lead author Anna Wåhlin, Professor of Oceanography at the University of Gothenburg.

In a scientific paper in Science Advances, the researchers report on the findings of this unique survey.

Some things are as expected. The glacier melts faster where strong underwater currents erode its base. Using the submersible, scientists were able to measure the currents below the glacier for the first time and prove why the western part of Dotson Ice Shelf melts so fast. They also see evidence of very high melt at vertical fractures that extend through the glacier.

But the researchers also saw new patterns on the glacier base that raise questions. The base is not smooth, but there is a peak and valley ice-scape with plateaus and formations resembling sand dunes. The researchers hypothesize that these may have been formed by flowing water under the influence of Earth's rotation.

Julia Wellner, a University of Houston faculty member in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, is a co-author on this paper and participated in the 2022 Antarctic field season when the AUV data was collected. Wellner is the U.S. principal investigator of the International Thwaites Glacial Collaboration project THOR, or Thwaites Offshore Research. She and her students recently completed four field seasons in the Amundsen Sea Embayment, where Thwaites and other glaciers, and the Dotson Ice Shelf, are undergoing rapid melting and retreat.

“The AUV that was used in this study, Ran, is also used for geophysical imaging of the seafloor,” Wellner said. She and her students normally would use AUV data to understand the record of glacial changes as recorded in the layers of sediment.

In this study, Wellner was able to work with Wåhlin and the other oceanographers on the deployment of the AUV underneath the ice.

“When the AUV was retrieved and the data downloaded, everyone on board the icebreaker was stunned to see the images from the base of the ice shelf. This study is the first to document the complicated morphology on the underside of an ice shelf,” Wellner said.

Complex Areas

Karen Alley, a glaciologist from the University of Manitoba and co-author of this multidisciplinary study, comments on the findings:

“The maps that Ran produced represent a huge progress in our understanding of Antarctica’s ice shelves. We’ve had hints of how complex ice-shelf bases are, but Ran uncovered a more extensive and complete picture than ever before. The imagery from the base of Dotson Ice shelf helps us interpret and calibrate what we see from the satellites,” said Karen Alley.

Scientists now realise there is a wealth of processes left to discover in future research missions under the glaciers.

“The mapping has given us new data that we need to look at more closely. It is clear that many previous assumptions about melting of glacier undersides are falling short. Current models cannot explain the complex patterns we see. But with this method, we have a better chance of finding the answers,” said Wåhlin.

Better Models

Dotson Ice Shelf is part of the West Antarctic ice sheet, considered to have a potentially

large impact on future sea level rise due to its size and location.

“Better models are needed to predict how fast the ice shelves will melt in the future.

It is exciting when oceanographers and glaciologists work together, combining remote

sensing with oceanographic field data. This is needed to understand the glaciological

changes taking place – the driving force is in the ocean,” said Wåhlin.

A Daunting Experience

Wåhlin continues: “There are not many uncharted areas left on Earth. To see Ran disappear into the dark, unknown depths below the ice, executing her tasks for over 24 hours without communication, is of course daunting. Experience from over 40 missions below ice gave us confidence but, in the end, the challenging environment beat us.”

The field work for this study was conducted in 2022. In January 2024, the group returned with Ran to Dotson Ice Shelf to repeat the surveys, hoping to document changes.

They were only able to repeat one dive below Dotson Ice Shelf before Ran disappeared without a trace.

“Although we got valuable data back, we did not get all we had hoped for. These scientific advances were made possible thanks to the unique submersible that Ran was. This research is needed to understand the future of Antarctica’s ice sheet, and we hope to be able to replace Ran and continue this important work,” Wåhlin said.

- Modified from University of Gothenburg article