Nature Paper Represents Deepest and Oldest Plate Remnants Reconstructed to Date

The Andes Mountains are the longest continuous mountain range in the world, stretching about 7,000 kilometers, or 4,300 miles, along the western coast of South America.

The Andean margin, where two tectonic plates meet, has long been considered the textbook example of a steady, continuous subduction event, where one plate slipped under another, eventually forming the mountain range we see today.

Reconstructing Andes Mountain Formation

In a recent paper, published in the journal Nature, a group of University of Houston geologists reconstructed the subduction of the Nazca Ocean plate, the remnants of which are currently found down to 1,500 kilometers, or about 900 miles, underneath the Earth’s surface.

Their results show that the formation of the Andean mountain range was more complicated than what previous models suggested.

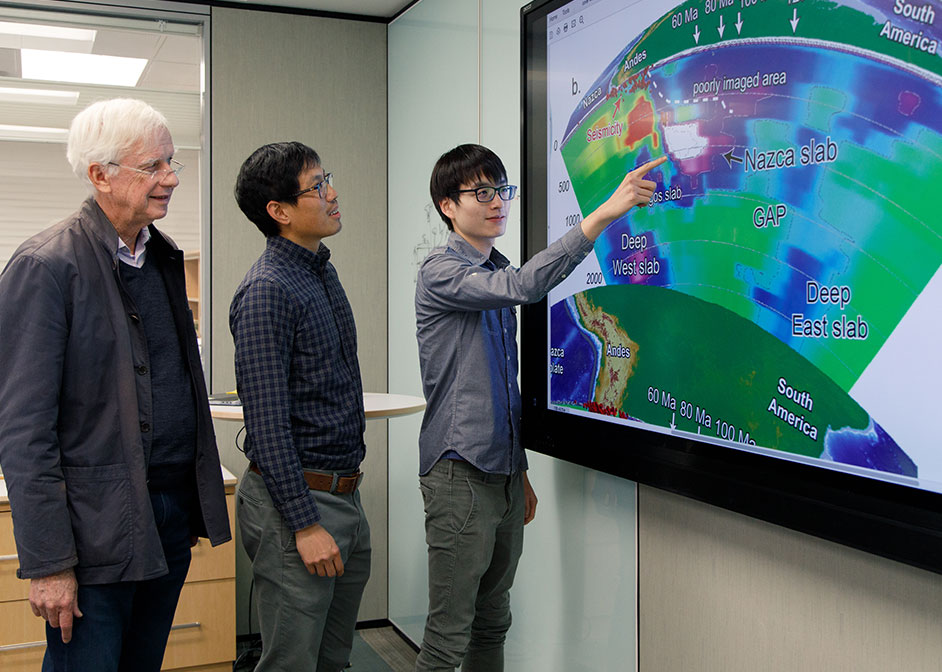

“The Andes Mountain formation has long been a paradigm of plate tectonics,” said Jonny Wu, assistant professor of geology in the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, and one of the authors of the paper. The lead author is Wu’s advised Ph.D. student in geology Yi-Wei Chen. Distinguished Professor of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences John Suppe is also a co-author. This article was selected for the cover of the Jan. 24 issue.

Plate Remnants in the Earth’s Mantle

When tectonic plates move under the Earth’s crust and enter the mantle, they do not disappear. Rather, they sink down toward the core, like leaves sinking to the bottom of a lake. As these plates sink, they retain some of their shape, offering glimpses of what the Earth’s surface looked like millions of years ago.

These plate remnants can be imaged, similar to the way CT scans allow doctors to see inside of a patient, using data gleaned from earthquake waves.

“We have attempted to go back in time with more accuracy than anyone has ever done before. This has resulted in more detail than previously thought possible,” Wu said. “We’ve managed to go back to the age of the dinosaurs.”

Nazca Plate Subduction

This latest paper represents the deepest and oldest plate remnants reconstructed to date, with these plates dating back to the Cretaceous Period.

“We found indications that when the slab reached the transition zone, it created signals on the surface,” Chen said. A transition zone is a discontinuous layer in the Earth’s mantle, one which, when a sinking plate hits it, slows down the plate’s movement, causing a build-up above it.

They also found evidence for the idea that, instead of a steady, continuous subduction, at times the Nazca plate was torn away from the Andean margin, which led to volcanic activity. To confirm this, they modeled volcanic activity along the Andean margin.

“We were able to test this model by looking at the pattern of over 14,000 volcanic records along the Andes,” Wu said.

The Center for Tectonics and Tomography

This work was conducted as part of the UH Center for Tectonics and Tomography, which is directed by Suppe.

“The Center for Tectonics and Tomography brings together experts from different fields, in order to relate tomography, which is the imaging of the Earth’s interior from seismology, to the study of tectonics,” Wu said. “For example, the same techniques we use to explore for these lost plates are adapted from petroleum exploration techniques.”

- Rachel Fairbank, College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics