Economic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Distribution of PPP Loans in Austin

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in unprecedented challenges to small businesses as well as to their employees. In 2020 the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) was established by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act (Pub.L. 116-136) as a way to mitigate the COVID-19 effects on businesses. The PPP, administered by the Small Business Administration (SBA), engages private lenders to disburse government-funded loans to small businesses to pay for expenses such as up to 8 weeks of payroll costs, including benefits. In January 2021 Congress authorized a second wave of PPP loans to prevent additional layoffs and business closures.

During the Summer of 2020, the Hobby School of Public Affairs in collaboration with the Austin Chamber of Commerce (ACC) conducted a survey of 1,050 business owners in the Austin area. The aim of the survey was to understand how Austin businesses were impacted by and responded to the COVID-19 pandemic.1 The survey also asked businesses about their financial needs and their experience with the first wave of the PPP. In this report, we analyze secondary data sources to further understand the impact of COVID-19 and the distribution of PPP loans in the Austin area.

Our main findings show that:- By April of 2020, industries in the Austin MSA experienced the largest employment

loss since the pandemic started. The industries that lost the highest number of employees

during this month were services as well as leisure and hospitality, both of which

have not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels. During this same month, around 29% of

the total PPP loans in the area were approved.

- Ethnic majority neighborhoods received on average fewer PPP funds than white-majority

neighborhoods.

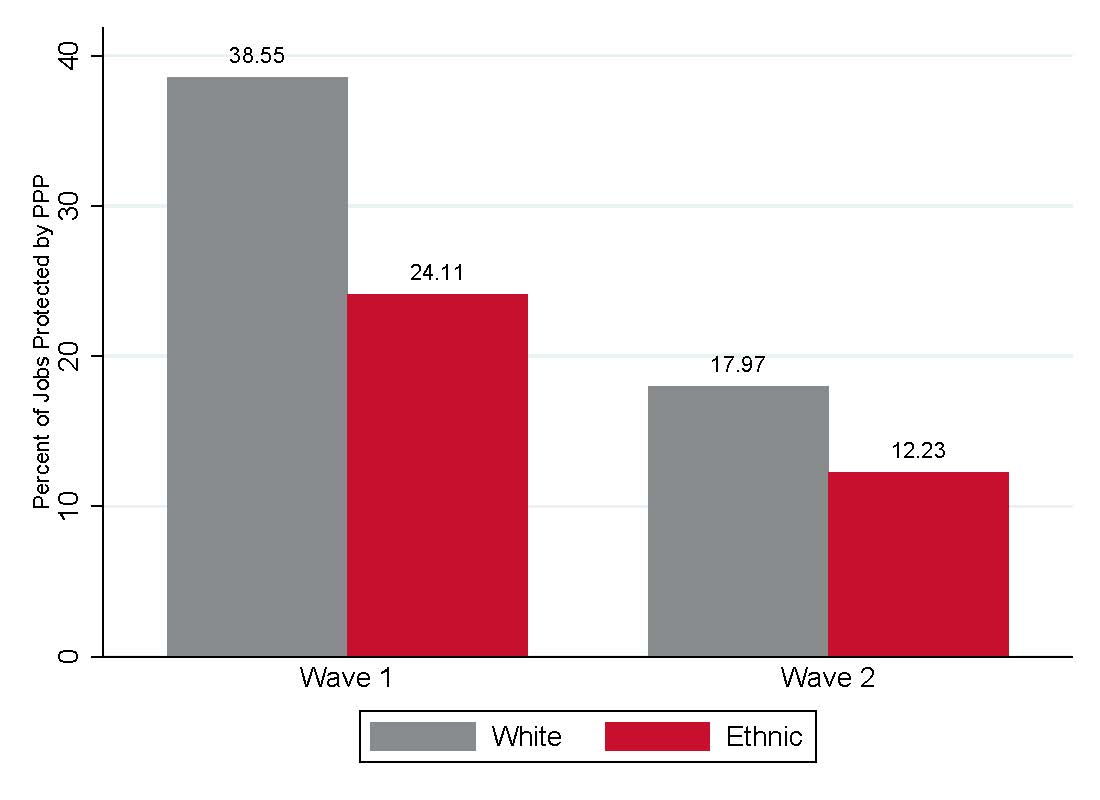

- The first wave of PPP loans in 2020 protected around 38% of the pre-COVID-19 jobs, more than twice the jobs protected in the second wave of PPP loans.

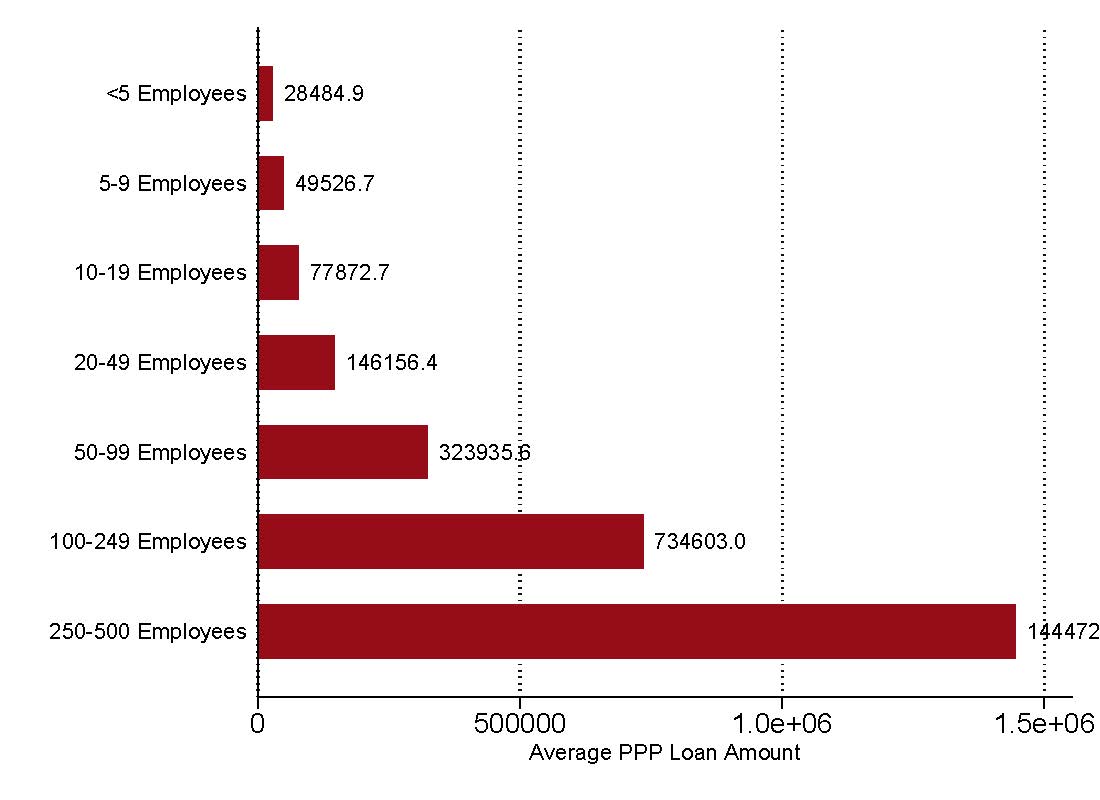

Figure 4.15: PPP loan average by the number of employees

Source: Reference USA and SBA-PPP (2021)

- On average, the first and second waves of PPP loans covered around 20% of the pre-pandemic payroll per worker. The difference in the amount of payroll covered across different neighborhoods was not significant.

Figure 4.3: Jobs protected by PPP in white and ethnic neighborhoods

Source: American Community Survey 5-year Data (2009-2019) and SBA-PPP Data (2021)

- Most of the industries that received PPP loans are in the sectors of professional, scientific and technological services, health care and social assistance, and other services.

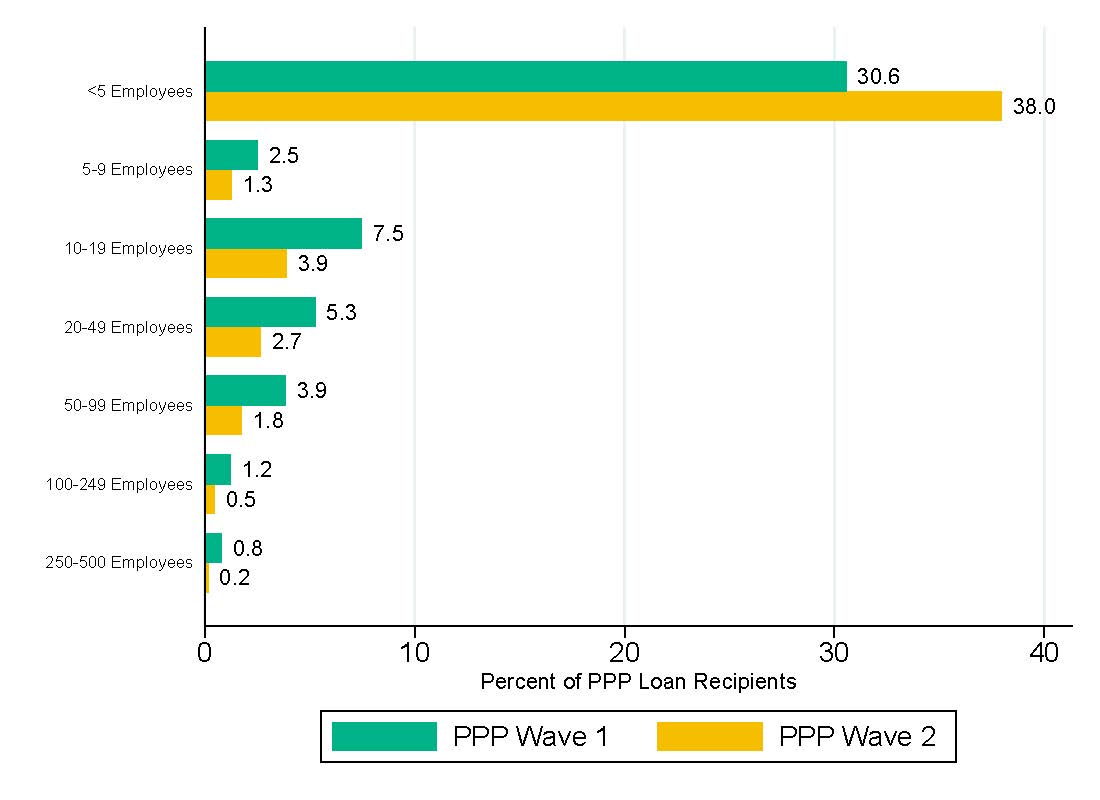

Figure 4.10: Percentage of PPP loans by number of employees in 2020 and 2021

Source: SBA-PPP (2021)

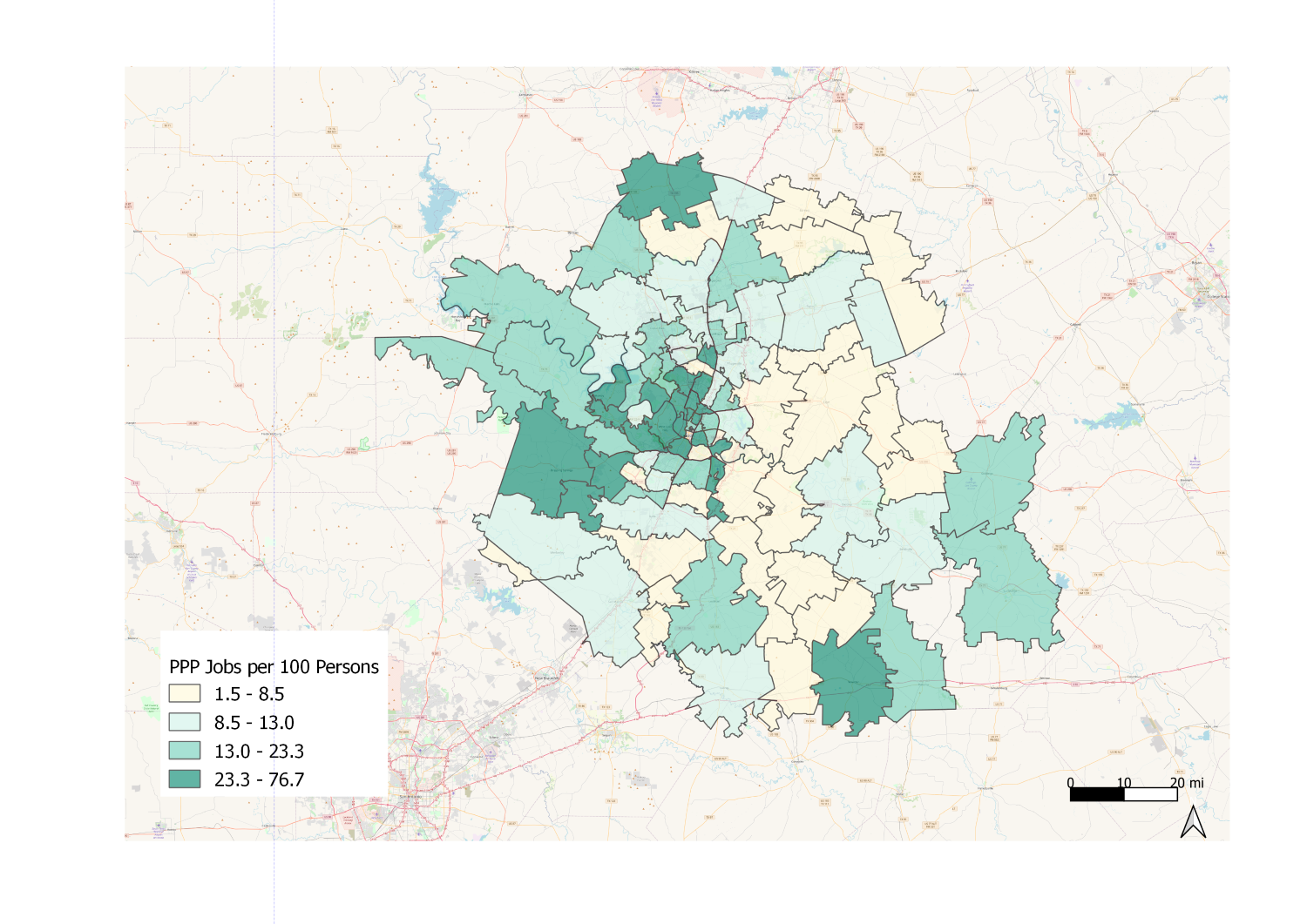

- Jobs and businesses receiving PPP loans are concentrated in white and high-income neighborhoods. The majority of businesses in ethnic majority neighborhoods are from the retail sector while most of the businesses in white-majority neighborhoods are in professional, scientific, and technical services.

Figure 4.7: Jobs protected per 100 persons

Source: Census Business Patterns 2019 and SBA-PPP (2021)

- In contrast with the first wave of PPP loans in 2020, the distribution of PPP loans in the second wave had less variance between ethnic and white neighborhoods as well as between neighborhoods with different income levels. Moreover, during the second wave of PPP loans, there was the highest percentage of small businesses that received the loan than in the first wave.

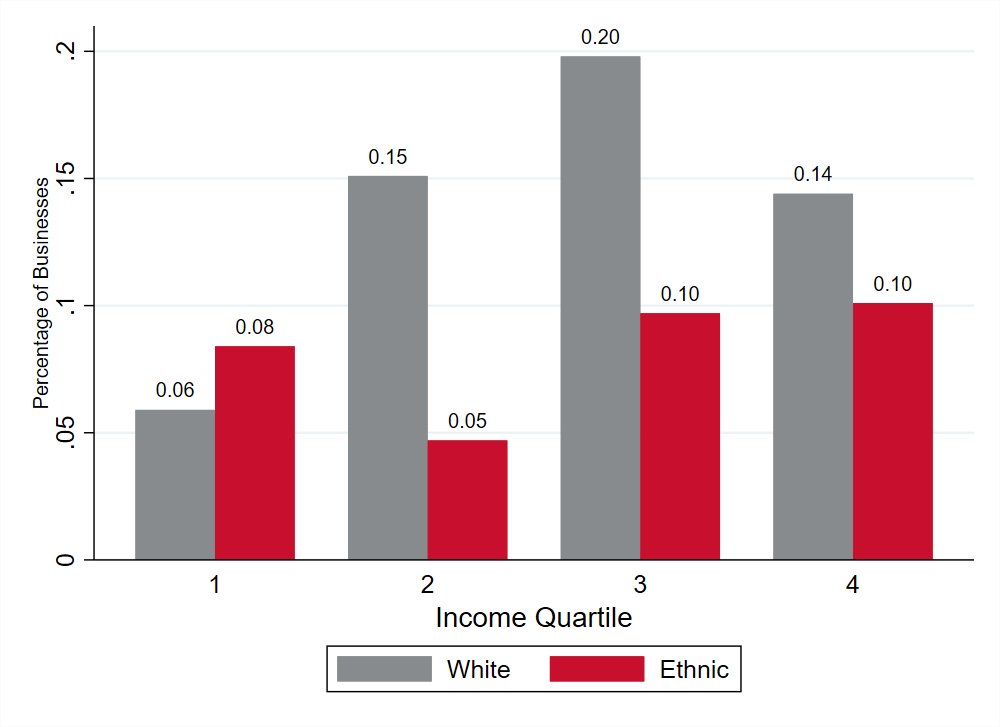

Figure 3.7: Percentage of businesses by size in white & ethnic neighborhoods

Source ACS 5-Year Data (2009-2019) and Census County Business Patterns (2019)

- As expected, companies with higher credit scores received more PPP money on average than those with lower credit scores.

The higher access to PPP loans by small and minority businesses in the second wave reflects efforts by ACC and other chambers of commerce in the Austin area, the city of Austin, state and federal agencies, including the SBA, to make the application process easier to navigate. Yet these patterns also suggest that lack of access to financial resources, including the PPP, at the early stages of the pandemic, might have pushed many small, minority- and women-owned firms out of business. The corollary is that providing sound responses to fundamental problems facing our communities demands careful attention to the rollout and implementation of the policy responses.

In the full report, we further elaborate on our analyses and findings. First, we present a summary of employment and business trends in the Austin and Round Rock Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) throughout the pandemic. Next, we briefly describe the baseline (pre-pandemic) economic and demographic characteristics of Austin. Lastly, we analyze how the PPP loans were distributed at the firm level and neighborhood levels.

Research Team

Gail Buttorff, Co-Director, Survey Research Institute, and Instructional Assistant Professor, Hobby School of Public Affairs

Yuhsin Annie Hsu, Research Assistant, Hobby School of Public Affairs and Ph.D. Student, Department of Economics

Yewande O. Olapade, Post-Doctoral Fellow, Hobby School of Public Affairs

Maria P. Perez Argüelles, Research Associate, Hobby School of Public Affairs

Pablo M. Pinto, Director, Center for Public Policy, and Professor, Hobby School of Public Affairs

Savannah L. Sipole, Research Associate, Hobby School of Public Affairs

Agustín Vallejo, Post-Doctoral Fellow, Hobby School of Public Affairs

Sunny M. C. Wong, Professor, Hobby School of Public Affairs