UH Researcher Joined Effort to Create a Ventilator Using Off-the-Shelf Components

See UH Photo Essay

As the spread of COVID-19 sparked a global search for ventilators to help critically ill patients, an international collaboration of particle physicists and engineers pivoted to design a mechanical ventilator made from readily available components.

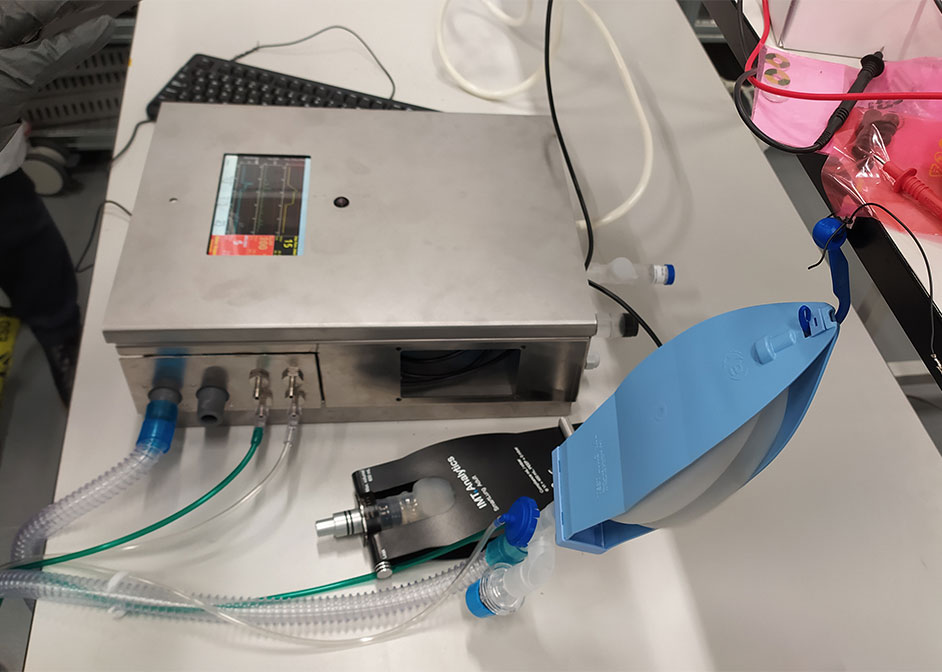

The ventilator, approved late last week by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for emergency use with COVID-19 patients, came together in about six weeks, driven by members of the Global Argon Dark Matter Collaboration. The international coalition studies dark matter, a mysterious substance that makes up about 85% of the matter in the universe but which cannot be directly observed.

Andrew Renshaw, assistant professor of physics at the University of Houston’s College of Natural Sciences & Mathematics and a member of the collaboration, now is working to ensure quality assurance of the controlling software and to connect the effort with U.S. manufacturers.

Minimal Components, Major Impact

The ventilator, known as Mechanical Ventilator Milano, or MVM, is made from a small number of off-the-shelf components in order to facilitate rapid production. Renshaw said its open-source blueprint and software is a reflection of the way scientists work.

“Whenever we do our science, we try to make it open to everybody,” he said. “In our typical day-to-day work, we’re really looking at fundamental science, trying to understand the origin of the universe. This is something that can be used immediately.”

Other members of Renshaw’s lab are involved as well, including post-doctoral researcher Paolo Agnes and graduate student Frank Malatino, who are working on the software that controls the flow of oxygen.

International Effort

The project began when Cristiano Galbiati, the spokesman for the Global Argon Dark Matter Collaboration, or GADMC, became part of the lockdown in Milan, Italy, the first European nation to be hit hard by the pandemic. Galbiati leads experiments with the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare’s Gran Sasso Laboratory, an underground laboratory in Italy. He also is a professor of physics at Princeton University.

As concern grew over critical shortages of ventilators, which pump oxygen into the lungs and remove carbon dioxide, members of the collaboration took on the challenge to design, develop, build and certify a safe, simple and powerful ventilator.

“It’s made to be as simple as possible to keep costs down, to keep manufacturing simple and fast,” Renshaw said. “The idea is it will be completely open-source. The hardware design, the parts list will all be available. The software itself will be open-source, too, available for any company that wants to manufacture it.”

Manufacturers will be allowed to make slight modifications but will have to share the changes so others can use them, he said.

“Italy was the first European country hit by this really hard. They went under lockdown right away,” Renshaw said. “I think (Galbiati) saw a niche, we have this expertise to design gas control systems, and so he just started assembling people and saying, let’s do this.”

Researchers from Italy, Canada and the United States are involved, among other nations, and prototypes are in place around the world to certify the ventilator’s effectiveness. The FDA approved the machine for use in the United States; it still must be approved in Europe, Canada and elsewhere.

“Moving at the Speed of Light…”

The work isn’t as much of a leap from dark matter as it might seem.

The GADMC uses detectors powered by liquid argon, which serves as a target for dark particles but which can become contaminated by the detector materials. Researchers purify the argon by converting it to a gas and filtering out the contaminants before returning it to a liquid state.

“This inherently requires a lot of gas control, rapidly controlling valves and constantly monitoring for levels of contaminants,” Renshaw said – expertise aligned with that required to design and operate a mechanical ventilator, which involves controlling the flow of oxygen and carbon dioxide to and from a patient.

The collaboration worked with engineers and other scientists on the project, he said. Anesthesiologists and other medical clinicians from Italy, Canada and the United States also provided guidance.

Galbiati, in a statement released after FDA approval, said the work highlights the benefits fundamental research can have for society. “It also highlights the importance of international and multidisciplinary collaboration to tackle the big challenges of this new era: at a time when borders between countries were closed and supply chains were disrupted, our collaboration across borders spread much faster than the virus, moving at the speed of light through the internet fibers,” he said.

More details about the design are available here. Information about a fundraising campaign are here.

- Jeannie Kever, University Media Relations