Researchers Collaborate on Highly Metastatic Form of the Disease that Carries Poor Prognosis

About 12 percent of women in the general population will develop breast cancer sometime during their lives. Of those who inherit the harmful BRCA1 mutation, 55 to 65 percent will develop breast cancer, while 45 percent of those with the BRCA2 gene will get it. Such inherited BRCA mutations account for approximately 5 to 10 percent of all breast cancers. While both genes are linked to inheritable breast cancer, the BRCA1 mutation is strongly associated with development of the TNBC subtype.

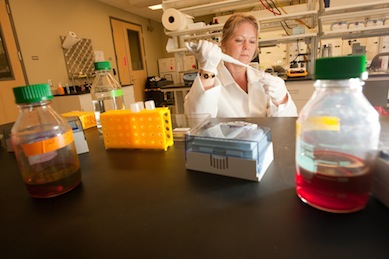

Working with the protein Maternal Embryonic Leucine-Zipper Kinase (MELK), which has been found to play a role in cancer, the UH research team is working to inactivate MELK in breast cancer cells in order to observe the effects it has on TNBC cells. By identifying changed functions and affected proteins, they recently have come to some conclusions about how MELK affects cells.

“It’s been shown that MELK is in its highest concentrations during cell division,” said UH biology senior Marisa Simon, who received an undergraduate research fellowship this summer to work on this project. “My hypothesis is that MELK safeguards cellular division by blocking the possibility of cell death. This blocking of cell death also can contribute to the longevity of cells. This gives researchers a potential target for cancer therapy. If MELK is essential to the division of cancer cells, then inhibiting it could inhibit and decrease tumor formation. Knowing what is affected by inactivating MELK will help researchers identify not only whether inhibiting it is effective, but also if it is safe.”

Collaborating with graduate student Fahmi Mesmar and led by assistant professor Cecilia Williams in UH’s Center for Nuclear Receptors and Cell Signaling (CNRCS), Simon says they have defined which other proteins and pathways MELK affects in TNBC cells, many of which relate to the death of cells and the cell cycle. The team is currently working on confirming these findings.

“Marisa has collected impressive amounts of interesting data,” Williams said. “The microarray analysis she performed, whereby she analyzed the effect MELK has on every single gene in our genome’s approximately 23,000 genes, has given us data for the impact of MELK on a global genome level. We are now working to decipher its impact to get a wide and complete understanding of what MELK does in TNBC cells, as well as how we can best use MELK to design better treatments.”

Found in both men and women, the MELK protein also may play a role in other cancers, such as prostate cancer. The researchers say MELK concentrations are high in stem cells and appear to protect them from dying. If MELK turns out to be a desirable target for cancer treatment, then inactivating it could be less hazardous to patients than conventional chemotherapy and radiation, which have pervasive effects on the body since they not only target cancer cells, but also other cells within the range of treatment. Since MELK inhibition would only be targeting the growth of stem cells, it would decrease these negative impacts.

“I’m interested in medicine and creating new therapies for cancer,” Simon said. “I found a mentor with the same passion, and she has allowed me to take part in her work. Through her mentorship and my own research, I have become interested and motivated to pursue finding a genetic therapy for poor-prognosis breast cancer.”

Williams says this research was initiated several years back in her lab, and research leading up to it has been published in the scientific journals Breast Cancer Research and Carcinogenesis. Her lab also has several other projects that relate to designing better treatments for breast cancer, including achieving a better understanding of how estrogen affects the development and growth of breast cancer and how certain microRNAs affect metastasis of breast cancer. These studies are connected to a large NIH-funded project the lab is doing on colon cancer, where estrogen and microRNAs also play a role and may be used to create better preventative treatments.

“Marisa has been a very good addition to my lab. She is full of enthusiasm, eager to do the work and has contributed to the direction of the project,” Williams said. “Her work is extremely relevant to my research of how poor-prognosis breast cancer functions, so that we can better understand how to target this type of cancer in the future.”

With her funding being extended to cover her senior honors thesis, Simon recently presented the research on MELK’s role in TNBC at UH’s annual Undergraduate Research Day in October. One of UH’s most prolific cancer researchers, Williams’ breast cancer research is funded, in part, by a grant to the CNRCS from the Texas Emerging Technology Fund.

- Lisa Merkl, University Communication