William Sager lectures to students aboard the R/V Falkor on a recent expedition to Tamu Massif, the world’s largest volcano.

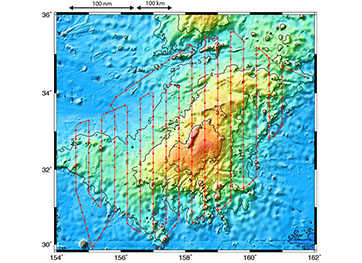

Plotted in red on a bathymetry map of Tamu Massif, the track of the R/V Falkor ship covered an area of nearly one million square kilometers.

UH geophysics professor William Sager led the latest expedition to Tamu Massif, the world’s largest volcano.

Covering an area of about 120,000 square miles, this volcano is roughly the size of the state of New Mexico. By comparison, Hawaii’s Mauna Loa – the largest active volcano on Earth – is approximately 2,000 square miles, or roughly 2 percent the size of Tamu Massif. The survey of this voyage covered an area of nearly one million square kilometers, which is roughly 386,000 square miles. The research team spent about 477 hours in the survey, gathering about 73 million bathymetric soundings and about 1.7 million measurements of the magnetic field.

The expedition was funded by the Schmidt Ocean Institute, National Science Foundation and National Geographic Society.

Leading the expedition was William Sager, who led the team of scientists that originally uncovered this massive volcano in the Pacific Ocean about 1,000 miles to the east of Japan. On board with Sager were seven UH students and two Texas A&M graduate students. This trip helped them gain valuable, hands-on experience that will prepare them for careers as geophysicists. The one undergraduate and six graduate students from UH are enrolled in a course called “Special Topics in Practical Marine Geophysics at Sea.”

Sager, a professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences in the UH College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, first began studying the volcano two decades ago and said this most recent trip to examine it was “tremendously successful, having sailed 98 percent of the planned track lines of an ambitious pre-cruise plan.”

Sager said his team came back with massive data sets that he and his students will now analyze. They also will be making a new magnetic anomaly map to show what parts of the volcano formed at what times. The existing data set consists of many dozens of oceanographic cruises that passed over Tamu Massif in the last 53 years.

“It looks like someone threw a plate of spaghetti at the computer screen,” Sager said. “That randomness, along with most of the cruises being from past generations before GPS navigation, has made the task of mapping the magnetic anomalies very difficult. We call this mess the ‘magnetic spaghetti monster.’ And with the grid of north-south magnetic lines we collected looking like the bars of a prison cell, we now have the monster penned up.”

Now, having had an opportunity to collect a grid of magnetic data using GPS navigation, Sager and students will be able to merge the pre-existing data with the new data, filling in gaps of the data coverage and formulating conclusions about the volcano’s formation.

Sager said there are two main hypotheses about how the volcano formed – the plume head hypothesis and the fertile mantle hypothesis. The plume head hypothesis states that volcanoes erupt because a huge blob of hot magma (plume) slowly rises from the boundary between the Earth’s core and mantle, finally erupting at the surface. This hypothesis would suggest short, fast eruptions, with magma spreading out widely in all directions. The fertile mantle hypothesis, however, implies lava oozing out of cracks and fissures in the tectonic plates, including oceanic spreading ridges. This hypothesis suggests more gradual eruptions with lava flows that do not go far from the ridges. Magnetic field measurements can be a key to deciphering this paradox because lava flows have magnetic particles that record the magnetic field direction at the time they cool.

“If we look at the two different hypotheses, they give us different expectations,” Sager said. “If Tamu Massif just formed at oceanic spreading ridges, we expect to see magnetic stripes formed parallel to the spreading ridge. But if we have a massive pulse of volcanism and the lava flows go long distances, then we wouldn’t see these coherent magnetic stripes.”

Another important component of this research cruise, Sager said, was to give students field experience. They’re now able to say they’ve been on a ship, with the opportunity to learn how to deploy equipment, how it functions and understand the process from start to finish. Students worked in shifts, keeping a cruise log and monitoring equipment. Between these shifts, they processed the collected data to get an understanding of what the instruments were recording and see the immediate results of the survey.

“The students learned a tremendous amount by being there and working on data,” said Sager. “Fieldwork is often an integral part of a geophysicist’s career. The students having an opportunity to see data they’ve collected at sea, gives them a very visceral understanding of what it really means.”

The five-week-long mission was aboard the R/V Falkor, which is owned and operated by the Schmidt Ocean Institute, a nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing ocean research, discovery and knowledge. In addition to the research, the cruise was a massive outreach project, coordinated with the Texas State Aquarium in Corpus Christi, in which scientists and students on the ship talked directly to more than 4,000 students and teachers on shore during the expedition, with many of these classrooms in Texas. The outreach efforts included ship-to-shore presentations, using the Falkor’s broadband capabilities, to inspire these potential future scientists.

“I wanted to show students the excitement of exploring the ocean bottom – often in places that nobody has been before – in hopes that they might consider pursuing oceanography or another science as a career,” Sager said. “We also were in regular communication with several museums, including Houston Museum of Natural Science and Aquarium of the Pacific.”

While results from this expedition will take months and years to decipher, Sager said they observed features in their bathymetry and magnetic data that give new clues about the development of the volcano. Though these findings are as yet quite preliminary, Sager says, they give him and his collaborators inspiration for their ongoing research.

###

About the University of Houston

The University of Houston is a Carnegie-designated Tier One public research university recognized by The Princeton Review as one of the nation’s best colleges for undergraduate education. UH serves the globally competitive Houston and Gulf Coast Region by providing world-class faculty, experiential learning and strategic industry partnerships. Located in the nation’s fourth-largest city, UH serves more than 42,700 students in the most ethnically and culturally diverse region in the country. For more information about UH, visit the university’s newsroom.

About the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics

The UH College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, with 193 ranked faculty and nearly 6,000 students, offers bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees in the natural sciences, computational sciences and mathematics. Faculty members in the departments of biology and biochemistry, chemistry, computer science, earth and atmospheric sciences, mathematics and physics conduct internationally recognized research in collaboration with industry, Texas Medical Center institutions, NASA and others worldwide.

To receive UH science news via email, sign up for UH-SciNews.

For additional news alerts about UH, follow us on Facebook and Twitter.