A deposit of nearly pure argon left undisturbed since Earth’s formation is about to help physicists understand more about the universe.

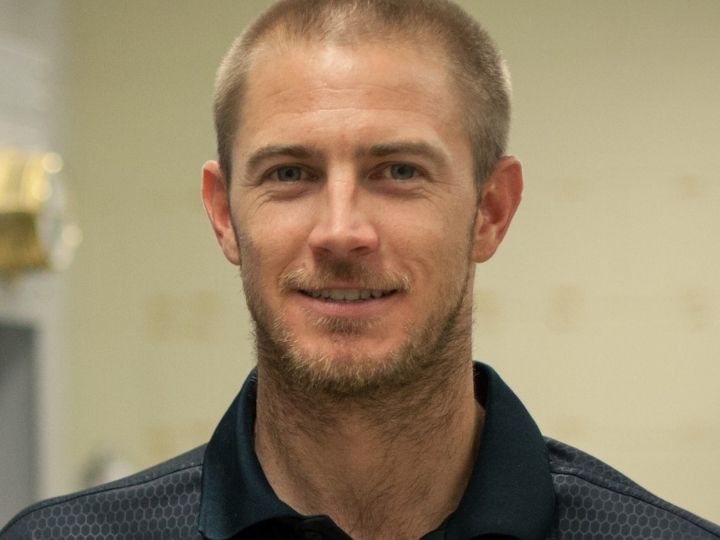

With a $2.9 million National Science Foundation grant, the Urania Project, led by Andrew Renshaw, University of Houston associate professor of physics in the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, will oversee installation and commissioning of an industrial-scale structure in southwest Colorado. At the same time in Sardinia, Italy, with support from the Italian funding agency Istituto Nazionale Fisica Nucleare (INFN), researchers will design and construct a specialized processing plant that will be shipped to Colorado.

Inside the combined facility – the processing plant constructed in Italy and outer structure built onsite by the Urania Project (named for the Greek muse of astronomy) – the argon will be extracted, purified and shipped to Laboratorio Nazionale Gran Sasso (LNGS) in Italy. There, it will be used in the search for answers to some of the biggest puzzles the universe presents.

But before the team can look outward among the stars, they first must reach deep inside the earth.

To be precise: They must see to the extraction and processing of argon gas found in a southwest Colorado natural gas drilling site operated by Kinder Morgan, a Houston-based drilling and pipeline company.

“Our facility will exist as a side function to Kinder Morgan’s Doe Canyon facility, which is already pulling CO2 (carbon dioxide) from the Earth’s mantle as part of its natural gas mining,” Renshaw said. “Contained within this CO2 stream coming from those deep underground Kinder Morgan wells is a small amount of low-radioactivity argon, which becomes a byproduct in their production of natural gas but is a tool that we can utilize. This is interesting because the low-radioactivity argon can be a major asset to our research, as it is a very nice element to use inside a low-background particle detector.”

Ultimately, the argon is separated from the carbon dioxide at Kinder Morgan’s site, then shipped in high-pressure cylinders specially designed for this project, to Sardinia, where it will be further processed then finally shipped to LNGS for insertion into the underground detector, called DarkSide‑20k.

“Once the argon is liquified, it can be used at the LNGS research site to detect particles according to how they interact with the liquid argon,” Renshaw said. Through those studies, the team hopes to piece together evidence of the universe’s dark matter and gain the ability to detect neutrinos from astrophysical sources.

Argon (abbreviated Ar) – colorless, odorless, tasteless – is listed on the far-right side of the periodic table with the other five “noble gases” (signifying they are inert, or nearly chemically unreactive). Being one of the most common of earth’s elements, argon is found almost everywhere. Scientists can harvest it easily from the atmosphere.

So why is this specific argon in Colorado so important to the Urania project and the DarkSide‑20k experiment in Italy?

“Because it is almost 100% argon-40, having been protected deep underground since the formation of the earth,” Renshaw explained. “During the same span of time, the atmosphere’s argon has been constantly bombarded by cosmic rays, loading it with argon-39, which then decays via beta emission and can cloud the DarkSide‑20k particle detector’s signals. This means that the argon extracted from deep underground in Colorado will allow DarkSide‑20k to be filled with almost 100% pure argon-40, greatly reducing the overall background rate of the detector and allowing for many sensitivity studies to be done.”

What the researchers hope to reveal with the DarkSide‑20k particle detector (expected to be in operation for a decade, starting in 2025), are signs of dark matter in the universe – what it is, how it behaves and why it exists. In other words, they hope to bring light to one of the darkest mysteries of the cosmos.