From 'Don't Say Gay' to Abortion Bans: The New Pronatalism

New Pronatalism THE PIVOT

—Elizabeth Gregory

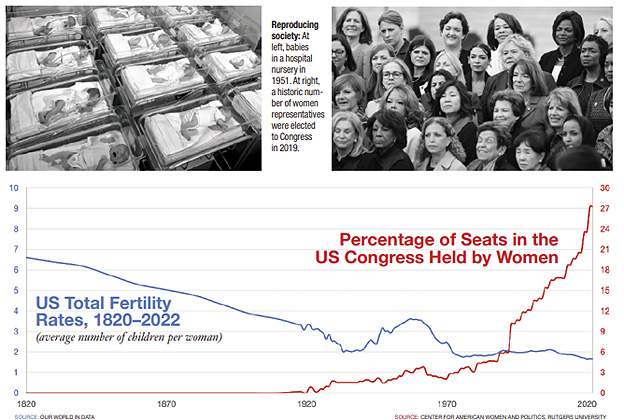

In the United States in the 19th century, it was not uncommon for pregnancies to begin early in a woman’s life and continue until menopause. Care of children excluded women from civic life, leaving them with very little say in the rules of the society they steadily reproduced. Only since the emergence of rubber barrier contraceptives in the mid-1800s, the availability of hormonal birth control in 1960, and the legalization of abortion in the US (in 1973) and elsewhere, have women (and men) around the world been able to reliably control their procreation. Unsurprisingly, the US fertility rate fell significantly over that period. But even after the 19th Amendment passed in 1920, enabling (some) women to vote, women’s representation in Congress remained less than 5 percent until the late 1980s (see the chart below). That began to accelerate only after the pill and abortion rights had been available long enough to allow sufficient numbers of women to delay or forgo having kids until they attained the education and experience needed for a political career. Since 2007, we’ve seen another major change in birth patterns in the US, reflecting among other factors the increased availability of even more effective birth control, including Plan B and long-acting reversible contraceptives, fueling an overall decline in fertility rates by 22.9 percent. That change includes a 68 percent fall in births to teen moms. This drop also reflects the fact that same-sex relationships are much more common. Per a recent Gallup poll, LGBTQ self-identification has grown from 2.7 percent among baby boomers to 19.7 percent among Gen Z (with 58 percent of LGBTQ adults identifying as bisexual).

These enormous shifts in fertility patterns have spurred two radical transformations: First, women have moved into electoral politics and policymaking roles in significant numbers over the past 30 years for the first time in American history, bringing with them major labor policy demands, including free childcare and wage equity. Second, young people with fewer babies to feed face less pressure to work. The need to keep unplanned arrivals fed, clothed, and housed has historically led many into low-wage jobs. But teens without kids can instead continue their educations or hold out for better wages. High school completion rates among young women rose between 2006 and 2021, particularly notably for Black women (from 83.9 to 95.5 percent) and Latinas (76.6 to 94 percent). These transformations are good news for young people. But they’re less welcome to employers or legislators who count on parental desperation to funnel young people into low-wage work and then hold them there for decades, to sustain profit levels or to make their state attractive through its “low cost of living.” Though advocates don’t describe them this way, anti-abortion policies clearly aim to push women both into more unplanned pregnancies and down the ladder of civic power. Likewise, anti-LGBTQ policies aim to push the growing numbers of young people who identify as LGBTQ back into the closet, and into heterosexual relationships and more pregnancies, planned and unplanned. In 2022, the teen birth rate in Texas rose for the first time in 15 years following the state’s 2021 six-week abortion ban, foreshadowing rises to come nationally in the post-Dobbs data.

Download Synopsis (PDF) | Article, The Nation