Ever since America’s oldest restaurant, the White Horse Tavern in Rhode Island, opened its doors in 1673, restaurateurs have been trying to keep their customers happy while increasing profits. Wine has always been a solid source of revenue for restaurants. But new research from the University of Houston finds the wine menu may be more important to the bottom line than the libation itself.

“In the old days, when you went to a fine dining restaurant, you’d have that nice leather book,” said Dennis Reynolds, dean of the Conrad N. Hilton College of Global Hospitality Leadership at UH. “But it was just a wine list, and it didn’t give you any information.”

In his study published in the Journal of Foodservice Business Research, Reynolds wanted to show that wine menus with more robust descriptions and food pairing suggestions would have more influence on the consumer than a list of the wines and their vintages.

“Consumers, if they engage and learn something from the experience, are more satisfied. And that's what we proved,” Reynolds said.

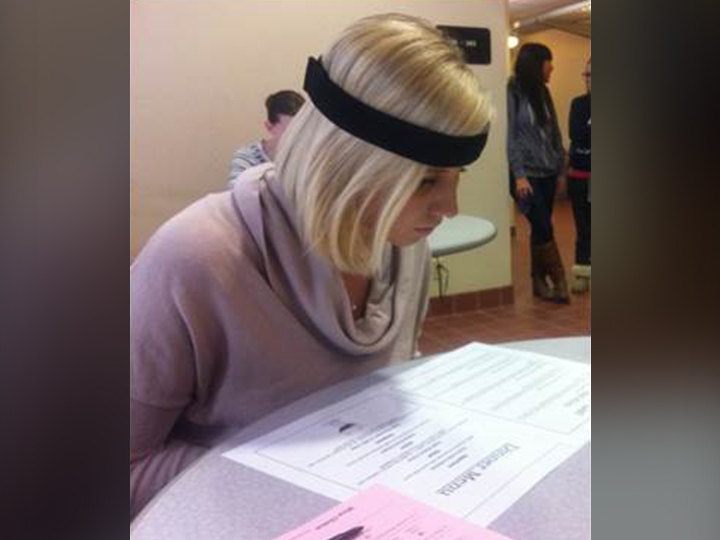

Reynolds and his students gathered 90 participants in a hotel ballroom and measured their cognitive responses to a variety of wine menus using brain-computer interface technology.

“Looking at brain activity, you're seeing them actually engage in the process,” Reynolds said. “The longer the better because that means the consumer is more involved with the menu, which is a good thing.”

The participants were given a prix fixe dinner menu and were asked to select a bottle of wine to go with it from one of three wine menus: the first with only vintages and prices, the second with descriptive information about the wine, and the third with the descriptive information and pairing suggestions.

“The second two, with the descriptions and the pairings, showed increased cognitive functioning,” said Reynolds. “The first one was dramatically different. People didn’t engage at all. The takeaway for restaurant operators is that you can do a pairing, you can do a description, either one is good. But you need to do one or the other.”

For Reynolds, the findings were clear that the more the participants thought about the wine and felt like they were making the right decision, the greater their satisfaction and greater the likelihood they would be more engaged the next time they dine in a restaurant.

“You can make food at home, but you want the whole experience,” said Reynolds. “And then when you put wine in the equation, that makes the experience much more gratifying.”

Reynolds’ goal now is to get his research into the hands of restaurateurs so they have a clearer picture of how consumers engage with wine menus. But he’s also ready to dive into the mind of the consumer a little deeper.

“The goal of applied research is to make a difference in the industry. That’s what I'm hoping we can do with this,” Reynolds said. “But I think we need to understand even more about consumer behavior to really optimize the industry, and that's where we're going.”