Doing the Work

Fatima Merchant, too, is focused on getting her research to people it can help, providing women newly diagnosed with breast cancer, and their surgeons, with information to guide their choices about reconstructive surgery.

“Now we can diagnose breast cancer very early, and we have patients in their 20s and 30s,” Merchant says. “That makes breast reconstruction a bigger deal.”

Insurance companies have been required to cover reconstructive surgery since the Women’s Health Care and Cancer Rights Act of 1998. “It is part of the treatment process,” says Merchant, associate professor of engineering technology and director of the Computational Biology and Medicine Laboratory at UH. “You can’t just treat the cancer and say, Go live your lives.”

Despite improvements in diagnosis and treatment, and growing knowledge about the way women are affected by body image, she says little research has been done about how women feel about their bodies following the disfiguring cancer treatments.

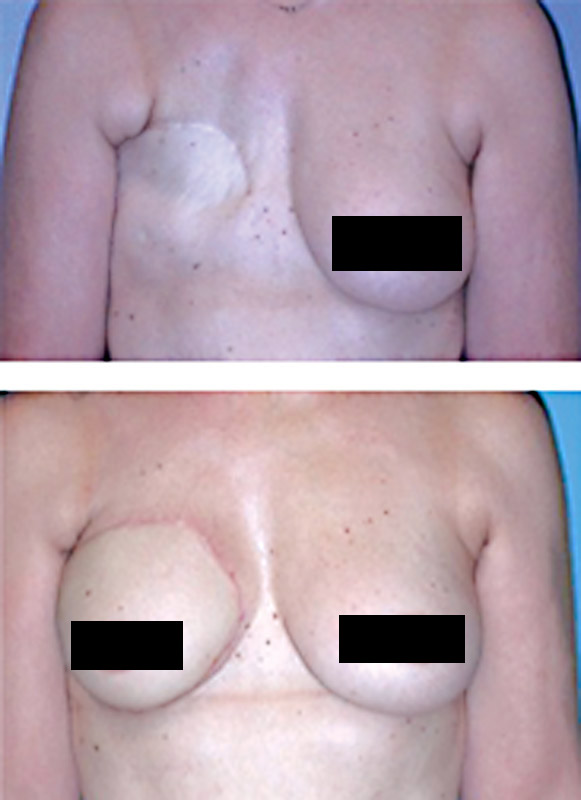

Merchant started the project nearly a decade ago, while working at a small biotech company in League City; at UH since 2008, she and researchers from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and UT-Austin are building a database of 500 women undergoing breast reconstruction, collecting their medical histories, demographic and physical characteristics and 3-D images taken before reconstructive surgery and at three months, six months, 12 and 18 months.

The database includes information about how the rebuilt tissue changes over time, as well as details that can’t be captured in a spreadsheet or 3-D image – how women feel about their new breasts.

It is, in many ways, uncharted territory. Breast reconstruction is complex surgery, sometimes lasting 10 or 12 hours and requiring multiple follow-up procedures over a period of years.

And women often have to decide about reconstruction – what type of implants to use, for example – while they are still reeling from a cancer diagnosis, Merchant says.

The database will allow women to view images of their peers, women with the same diagnosis and demographic factors, to get an idea of what to expect, including what their reconstructed breasts will look like and how they change over time.

“It will be less scary if women know what to expect,” she says.

Another goal is to develop the technology in a format that would allow surgeons to take it into the operating room, offering a visual guide and concrete measurements to help with the surgery.

Merchant, who also has faculty appointments to the UH departments of computer science, biomedical engineering and electrical and computer engineering, provides 3-D modeling and analysis for the project, including developing software for measurement and analysis. The other principal investigators for the multidisciplinary project, funded with a $3.4 million, five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health, include Mia Markey from UT-Austin and Michelle Fingeret from MD Anderson. The team’s expertise ranges from engineering and bioinformatics to psychology, plastic surgery and decision-making.

Few women have the time – or the skills – to conduct their own research before embarking on reconstructive surgery.

“We put it all out on the table,” Merchant says.

Laying it all out meant something different for Laura Turchi, whose book “Teaching Shakespeare with Purpose: A Student-Centered Approach” was published in January.

While most collaborations are structured similarly to Merchant’s group – people from different disciplines, each focused on a specific piece of the problem – Turchi and her coauthor decided to work holistically, each taking part in every decision.

“We sat next to each other physically for many weeks,” she says. Other chapters were written collaborating via Skype. “It was blood from a turnip, getting every word out.”

Turchi, assistant professor of curriculum and instruction in the College of Education, wrote the book with Shakespearean scholar Ayanna Thompson of Georgetown University, combining a deep understanding of Shakespeare’s works with modern studies of race, gender, history and other issues relevant to 21st century students.

The academic partners, one an expert on today’s students and how best to teach them and the other a researcher who specializes in the study of Shakespeare, met at Arizona State University, their offices just down the hall from one another. Both left Arizona in 2013, Turchi for UH and Thompson for Georgetown.

Deciding to write this book is, Turchi jokes, “our origin story.”

She had returned to her office at ASU one day in 2012, frustrated after observing a student teacher try to teach Shakespeare to a high school class. “The students were just dying, they were so bored,” she says. “The teacher was also dying,” unable to convey what he knew.

Thompson, meanwhile, was fretting over graduate students assigned to teach Shakespeare to undergraduates. They were so wrapped up in technical analysis, she told Turchi, they had lost any perspective on purpose.

“Ayanna and I both care about teaching and pedagogy, but we love the plays,” Turchi says. “It’s terrible to see them rendered boring.”

Shakespeare, she says, is “rich and complicated and engaging.” Not boring. And his work remains relevant, with its explorations of identity, prejudice and other human emotion.

Originally, Turchi and Thompson planned to teach a class together. That shifted to writing a book after they moved to separate universities. And they decided not to take a traditional path.

Writing, after all, is normally a solitary pursuit. Co-authors generally take ownership of separate chapters, perhaps sharing editing. They wanted this book to be different.

“We were very ambitious that it represent both 21st century scholarship on Shakespeare as well as how to lead learners to what they need to know,” Turchi says.

They came at the subject from different corners. Turchi was interested in what skills students need to read difficult material. Thompson wanted them to be ready to understand Shakespeare’s plays from any angle, not just the angle covered in class.

“We had to learn each other’s language,” Turchi says. “The challenges are similar, but the language is different.”

They bridged the differences, despite the geographic distance, traveling to London in 2014 to talk with experts at the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Globe Theatre and elsewhere, asking about educational outreach, teacher training and other projects. Back in the United States, they talked with people at the Folger Shakespeare Library and with theater companies that work to connect with students and schools.

That summer, Turchi spent weeks at Thompson’s home in Washington D.C., sitting together as they hashed out chapters. They argued, but they also took ownership.

“It was so much fun,” Turchi says, “even though it was hard.”

Next Story:

The Valley of Death

Associate professor of pharmacology, worked with doctoral student Craig Vollert to develop and commercialize a chemical treatment to make staining tissue samples more effective.