Today, our guest, UH journalist Michael Berryhill, looks at the Lucifer effect. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In April 2004 Philip Zimbardo saw those first chilling pictures from the American prison in Iraq called Abu Ghraib. Zimbardo froze in disbelief at the sight of American soldiers, some of them women, gleefully posing beside naked Arab prisoners. One of the images, of a hooded, robed man standing on a box with electrical wires coming out of him, would burn itself into the world's memory.

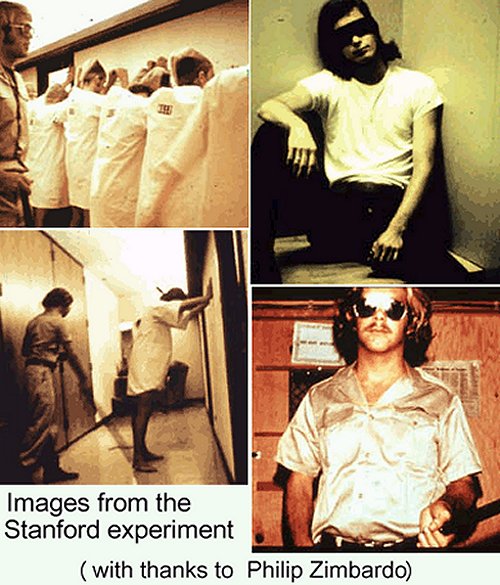

As soon as the photos were revealed to the public, the chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff, General Richard B. Myers, disavowed them as the isolated work of a few "bad apples." How could Myers know that Abu Ghraib was the matter of a few bad apples when he hadn't yet conducted a thorough investigation? Zimbardo had a different hypothesis, for he had designed one of the most famous experiments in social psychology: the Stanford Prison Experiment.

In the summer of 1971, Zimbardo randomly assigned a group of carefully screened male college students to play the roles of prisoners and guards in a mock prison in a basement at Stanford University. The Viet Nam war was going on and was being vigorously protested. Asked their preferences, most of the students wanted to be prisoners. Some of them figured the experience would come in handy if they were arrested at a demonstration. They expected a low-key experiment where they might relax, read a little, meet some new people and maybe learn something about themselves.

What they got was hell. The guards took to their duties with an unanticipated appetite. While they were not permitted to physically abuse the inmates, the guards were encouraged to assert their authority, and assert it they did. They banged on the cell doors, belittled the inmates, kept them awake all night, forced them to clean toilets with their bare hands, sexually humiliated them and made their lives so miserable that within 36 hours one of the "prisoners" cracked up and had to be released.

Even Philip Zimbardo, who designed the experiment, became a captive of his prison. Although his inmates were deteriorating and his guards were growing more abusive, he was determined to keep the experiment going.

An outsider saved Zimbardo from his creation. He brought his fiancée, a psychologist who had just earned her doctorate to interview some of the inmates. After sizing up their mental state, and seeing Zimbardo's fierce determination to continue, Christina Maslach took a heroic stance. She demanded that he call it off the experiment and, to his credit, Zimbardo complied.

The main lesson of the Stanford Prison Experiment was how quickly good people -- even those with doctorates in psychology -- can collaborate in doing evil to others. The abuse at Abu Ghraib shook Zimbardo so badly that he recently published a book called The Lucifer Effect, Understanding How Good People Turn Evil. The next time we hear talk about a few bad apples, we might remember what Zimbardo learned, that bad apples are not always the problem. Sometimes it's the barrel that holds them.

I'm Michael Berryhill, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

P. Zimbardo, The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil.(New York: Random House, 2007)

For more on the Stanford Prison Experiment, see: http://www.prisonexp.org/

Michael Berryhill is assistant professor of journalism at the University of Houston's School of Communication. Before joining the faculty in August 2006, he worked for 27 years as a writer and editor for Texas publications, including the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, the Houston Chronicle, D and Houston City Magazine, and Texas Parks and Wildlife Magazine. His freelance journalism has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Harper's and The New Republic.

(clipart)