Today, we finally reach Timbuktu. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I say finally because, all my life, I've dreamt of seeing Timbuktu. It's unlikely I'll really ever get there, but you and I can at least make the journey today in our imaginations.

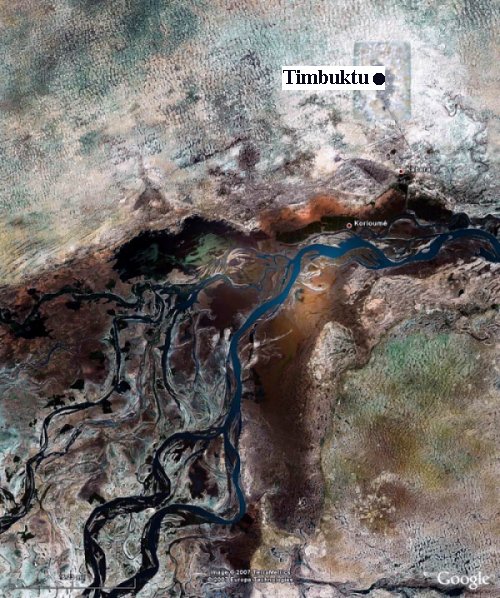

Timbuktu might take its name from an 11th-century woman Buktu; and the word tin (not tim) means a place. Passing merchants (mostly Tuaregs) knew Buktu to be unshakably honest. They could entrust her to store their goods. She may've laid the foundation for this trading center in the southern Sahara, nearly a thousand miles east of Dakar and the Atlantic and just north of the Niger River.

As caravans moved through Timbuktu carrying salt, gold, ivory, and other goods -- including slaves -- the city grew wealthy. During the 14th through 16th centuries, it was the seat of three successive empires. It was connected by canal to the Niger River.

With wealth came learning: Traders brought books, and scribes copied them as they passed through. Schools and universities arose. Timbuktu became a great center of learning as well as commerce. But her downfall, as well as her rise, involved slavery. When Europe took it up, African slavers set up huge trading enterprises on the West African coast. The city's economy weakened and, in 1591, Moroccan invaders were able to take it over.

They wanted Timbuktu's wealth and saw only a threat in all that accrued knowledge. By then, Timbuktu housed 120 libraries. So the invaders threw out the learning establishment -- books, scholars. Of course, many people hid books away -- buried them or sealed them in mud walls.

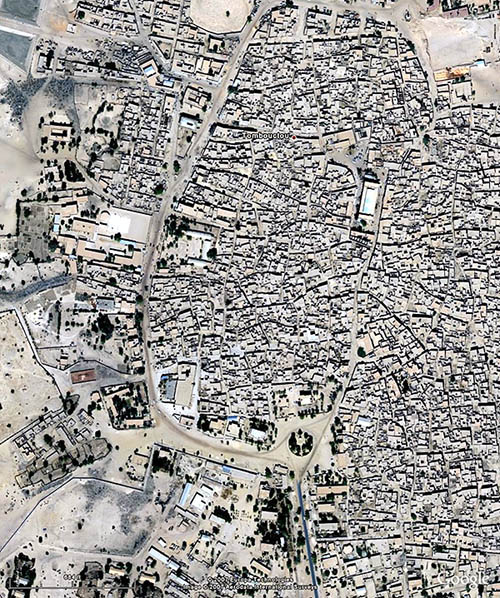

Today, this remote and impoverished city is rich in some 14,000 old books that've literally come out of its woodwork. Scientific historians who converge upon Timbuktu have only dented the task of translating the old science texts from Arabic and other less know languages. They find that Timbuktu's medieval and renaissance scholars followed a path separated from Europe.

Their astronomers didn't follow the European leap to a sun-centered solar system, but they sprang far ahead in the mathematics of calendar writing -- far ahead in trigonometry. The writings detail astronomic events six hundred years ago. Scholars, racing to translate this huge trove of literature, now wonder what these ancients knew of medicine, botany, chemistry and climatology. How did the knowledge of other regions flow through this glittering outpost? How much new science did it create?

South African astrophysicist Thebe Medupe thinks Africa would do far better in science if Africans realized that the Sub-Saharan world, just a few centuries ago, held a great intellectual center.

But, the romantic image is hard to get around. In a recent survey of young Britons, a third thought Timbuktu was imaginary. The rest found the very name to be mystical. For most of us it remains a location in our imaginations -- not in geography or history.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

C. Abraham, Stars of the Sahara. New Scientist, 18 Aug., 2007, pp. 39-41.

M. de Villiers and S. Hirtle, Space, Time, and Timbuktu. Natural History,July/August, 2007, pp. 22-26.

For more on Timbuktu see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timbuktu and http://www.thesalmons.org/lynn/wh-timbuktu.html

And for more on Timbuktu's books, see:http://international.loc.gov/intldl/malihtml/malihome.html

The successive satellite views of Timbuktu below are all courtesy of Google Earth: